Examining the Era of Micro Trends

Just when you thought you’d perfected ‘Balletcore’, you find out it’s ‘Tomato Girl Summer’. But not for long. Next calls for a focus on the ‘Frazzled English Woman’ trend, before this is swiftly replaced by the ‘Coastal Cowgirl Core’. The 2024 ‘Mob Wife’ aesthetic is seemingly already old news, as is ‘Bogcore’ (i.e. “viking-meets-grunge-meets-organicore”, of course). A quick skim of Aesthetics Wiki and you’ll find hundreds of previously inconceivable so-called ‘cores’ and ‘aesthetics’ that simply didn’t make it to your hyper-personalised algorithmic feed. And just as they catch your attention, the internet has moved on.

Today, the zeitgeist is in many ways elusive.

Prevailing trend categories have always existed, but historically these notions defined decades as opposed to a singular week on social media. We are now in the era of micro trends.

“A niche or industry specific consumer behavioural trend which is mass market ready and actionable. With a shorter life span, micro trends usually filter down from Macro Trends and provide opportunities for innovators, designers, and marketers to tap into these emerging consumer mindsets.”

Micro trends often take already common notions and make them marketable, for example, ‘Cinnamon Cookie Butter hair’ is simply a new way to market brunette hair.

For those trying to keep up with them through clothing purchases, micro trends have such short lifecycles that the latest trend might be old news by the time the parcel has even arrived on your doorstep.

Natalia Christina, director of strategy at creative agency The Digital Fairy, said in an interview with The Face Magazine: “A perfect (and troubling, for the environment) mixture of the need to satiate our feeds with ‘newness’ coupled with access to a never-ending vault of nostalgia (aka the internet) means trends are being coined almost daily.”

Ubiquitous to social media and more specifically, TikTok, micro trends differ quite drastically from subcultures, which traditionally came with not only an aesthetic but a broader value system. Throughout the years, fashion subcultures have organically evolved, fuelled by shared interests in music, literature, art, or political ideas, particularly within youth communities. Cast your mind back to the likes of the hippie, punk, or grunge movements which led to significant cultural shifts.

Post-subcultural thought challenges the traditional understanding of subcultures, suggesting that they either no longer exist or have become indistinguishable from mainstream culture due to mass consumption and globalisation. Traditionally, subcultures challenged the mainstream but now micro trends, cores, and aesthetics are in fact the mainstream.

Exploring the ‘core-ification’ phenomenon delves into the heart of the subculture discourse. Real subcultures, which traditionally go beyond mere aesthetics to embody specific beliefs and values, face a challenge. As trends become more commercialised, the risk of losing the original meaning and depth associated with subcultures grows. Understanding and respecting the values attached to subcultures becomes crucial to preserving the richness of societal diversity and maintaining authentic cultural expressions.

According to a recent report from Day One Agency: “…the “communities” they briefly foster are fickle, leaving participants in a state of vertigo, stumbling from one Ephem-era to the next. An Ephem-era is a commerce-enabled mirage: by the time you’ve joined in a trend, it’s already gone. The closest thing to a “community hub” is a well-used affiliate link.”

Fashion aesthetics are nothing new, but their popularity reached new highs during quarantine. Technology and digital accessibility have changed the trajectory of trends. With a multitude of trends defining a single week.

A common thread throughout youth culture is the search for identity, validation, and a feeling of belonging. Traditionally, subcultures may have indeed offered an antidote to these needs – giving participants a sense of community and purpose with like-minded individuals. Today’s vague, elusive, and ever-changing trends which exist primarily on mobile phones, do not offer the same kind of experience.

Mireille Silcoff, poignantly said in the New York Times: “Kids are not failing by wanting to be cottagecore or meatcore or this new preppy. It’s the culture available to them that is failing, by no longer being able to connect any of these categories with lived experience or social meaning.”

Not only is it unattainable for people to stay abreast with every micro trend, the ‘clean girl’ aesthetic and ‘quiet luxury’ trend are just some examples of how these micro trends can be deeply exclusionary and problematic. In an article for Byrdie, Ariane Resnick outlines the ways in which the ‘clean girl’ aesthetic is classist, fatphobic, racist, and ageist. Oni Chaytor wrote in The Blackprint about the appropriation of this trend, saying: “…the concept of what TikTok has called “a clean girl” has existed in Black and Brown communities for hundreds of years.”

Furthermore, microtrends contribute significantly to the issue of overconsumption in the fashion industry, as companies are increasingly designing and producing clothing within just a couple of weeks to keep up with trends.

The accelerated pace of trend cycles results in clothing items designed for quick, disposable use, often worn only once or twice before being discarded.

A common destination for such clothing is the Kantamanto Market in Accra, Ghana, where, according to the Or Foundation, about 40% of the clothing leaves as waste. The flow of material and the space that this material ultimately occupies clearly follows colonial power dynamics.

The ultra-fast and low-cost approach adopted by many companies might contribute to the commercialisation of subcultures without preserving their original values, undermining the cultural depth associated with genuine fashion expressions rooted in subcultures.

Writing in Good on You, Maggie Zhou noted: “Not every micro trend is evil. In fact, many of these looks might inspire us to dig deeper into our closets and rediscover items we haven’t worn in years. Or maybe it drives us to rescue some garments from a local charity shop.”

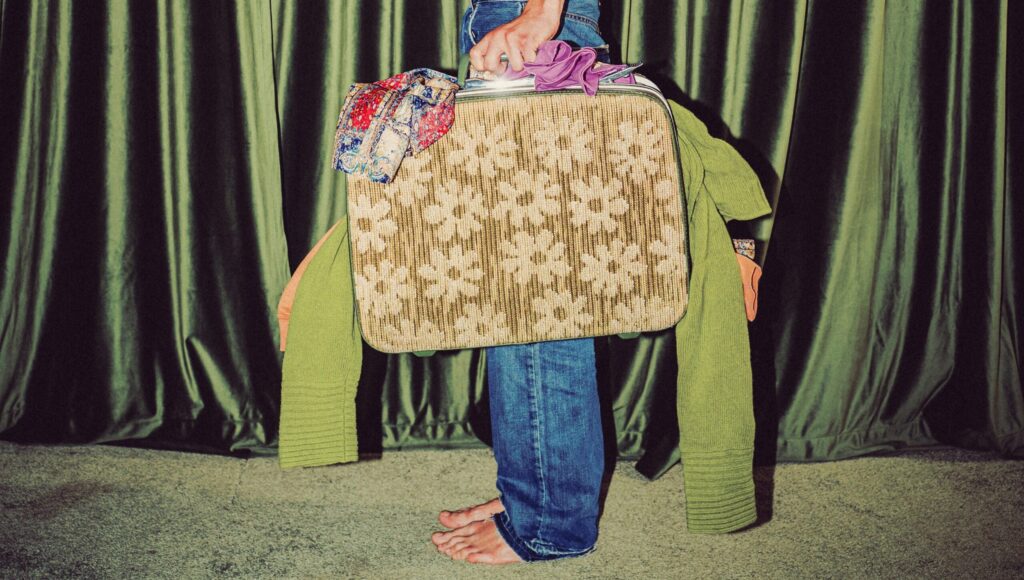

A resolution to the constant stream of micro trends is a deep exploration of personal style. The intrinsic joy of fashion is often eradicated when clothing is viewed as so disposable and the trend that it conforms to is likely to expire by the end of the month. Much relief can be found by stepping out of this relentless trend rotation and considering the clothes that truly appeal to you.

You have the ability to be powerful with your purchases. Every time you opt for one garment over another, you incentivise brands to continue with the practices behind the item. Investing in brands that prioritise environmental, social, and circular sustainability is crucial.